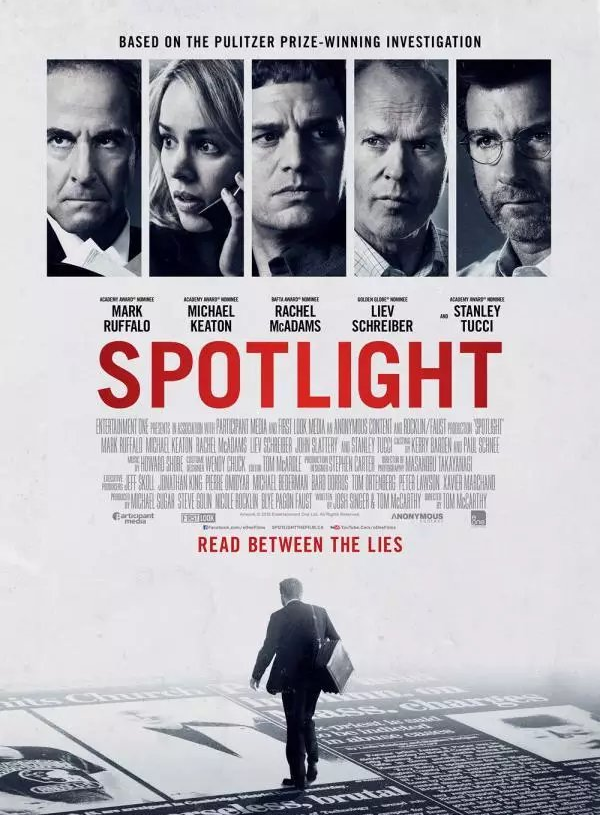

The 88th Academy Awards ceremony took place on the evening of 28 February (2016) local time in the United States. Spotlight, a biographical drama starring Michael Keaton and based on true events, took home two Oscars this year, for Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay.

It is an Oscar-winning film and one that deserves a sinking moment of reflection from those in the media.

It doesn’t need to be climactic, nor does it need to be a characterisation, it just needs to be true to what really happened, and that’s enough to shock people.

This biographical drama, starring Michael Keaton, is based on a Pulitzer Prize-winning story published in the Boston Globe in January 2002 about the rampant sexual abuse of boys by priests in American Catholic schools.

In the film, Keaton is Robbie Robinson, the veteran editor of the paper’s “Spotlight” investigative unit, whose prototype, Walter Robinson, said after seeing the film, “Seeing Michael Keaton as myself made me want to apologise to so many people I’ve interviewed.” He also joked, “If Keaton had gone to rob a bank, the police would have come and taken me away soon.”

Robinson’s film character comparison piece in the Boston Globe mentioned that this wasn’t the first time he’d seen Keaton play a media personality. Back in 1994, Keaton played an editor who writes front page headlines with the help of his wife in the film The Paper.

Unlike the high-energy chatter of the American drama The Newsroom, Spotlight’s director Thomas McCarthy boils the frog in warm water, moving in layers of meticulous logic, so that by the time you look back, you are swept up in the vast system of demons behind the story and are unwittingly caught up in it. The film pursues not just the truth of one case, but the entire Catholic system of top-down cover-up and connivance.

In 2001, the story begins with a long-sheltered case of child molestation by a Catholic priest, and a new editor-in-chief orders a focused investigative team to expand the urban story into an in-depth investigation. Thus, in the Boston area alone, the priests involved expanded from the 13 initially extrapolated by a support group of victims, to the 90 predicted by the treating doctors, to the 87 by the investigative team doing exclusions based on the priests’ work logs, until finally cross-referencing pinpointed 70 child molester priests who had privately reconciled with their victims.

It is only at this point that the viewer follows with alarm: it turns out that God has not only handed over a tempting cone of ice cream, but has also reached deep into the boys’ trousers with his hand of darkness. These children are distinctly poor or shy, the youngest being four years old and too ignorant to even say “no” to the hand of God.

The most frightening thing is that the parents’ resistance and complaints are silenced by the bishops and lawyers, with minimal hush money, and access to the media, leaving the priests on “sick leave” or “reassignment” to the next one. The priests were left on “sick leave” or “reassigned” to the next parish where they would “give the children ice cream”. When the investigating team confronted one of the priests, he said, “Yes, I did it”, with a chillingly sparse look in his eyes. He is even more unapologetic about the difference between his methods and rape, having been raped himself as a child.

The film is full of traces of the old days of flip phones and crossword notepads, and the journalist’s investigative methods are fairly straightforward: researching materials in libraries, flipping through newspaper clippings, filing public documents in court, and tracing pages of a priest’s workbook. …… The process of uncovering the mystery follows the most basic investigative reporting sequence – get a lead, decide on a topic, find out what happened. -Get a clue, decide on a topic, follow up, and carefully seek proof. The members of the Spotlight team seem to be more truthful than today’s “editorial posters” and “journalists”.

I admire the dedication of the main cast, including Keaton, from mimicking the Boston accent of the prototype journalist, posing at their desks with their wives, to what brand of nail polish the only woman on the team wears and what colour sticky notes she likes to use, to the point where I thought I was watching a documentary.

Keaton puts away the bravado of his Birdman days, but reveals his movie star nature with a line of tears at the doorstep of an old friend’s house at the end. Rather than highlighting a specific character, the film uses group scenes to build a fervent editorial room that confronts an ugly system and doctrinal authority.

It was actually a bit of a surprise to see a film dealing with religious beliefs during awards season. There are two things I like most about this Best Picture Oscar winner. Firstly, the precision with which it cuts child molestation and homosexuality from their essence, without a hint of ambiguity, with the trifling words of a gay teenager growing up on a park boulevard.

Then there is the examination and introspection of the inertia of thinking by those in the media, led by Keaton. The more explosive information you receive as an editor or journalist on a daily basis, the greater the blind spot in your thinking and the more difficult it is to step outside the safety zone. In the film, for 34 years, although everyone vaguely sensed that something had happened, there was little in-depth coverage of the child molestation case, and even if they did see it, it was only a trip to the court, a circular, and ignoring the report letter, which indirectly led to the tragedy that cast a shadow over hundreds of people’s childhood.

The four-page list of cities where major sex abuse scandals have occurred at the end of the film makes one thing clear. It takes a village to raise a kid, it also takes a village to abuse one.