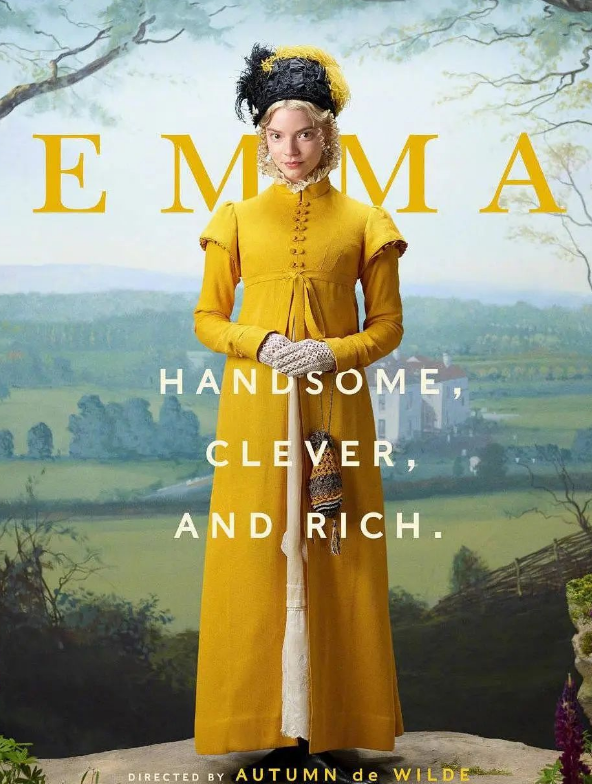

Emma has been adapted more than once, whether in the 1996 film, the 2009 BBC miniseries or the 1995 modern school comedy The One and Only, and the character of Emma has become more and more distinctive in each rendition, while this modest adaptation seems banal.

Nevertheless, the exploration of the romantic comedy form in Emma is noteworthy, not to mention the divine face of Anya Taylor-Joy coupled with a costumed score that is played to the hilt, making this a must see for those who enjoy Austen or lighthearted romance films.

Romantic comedy: restoring the romance of Austen’s writing

Emma Woodhouse, the daughter of a wealthy squire, claims she is not interested in love but is keen to match friends. As her friends are set up for marriage, Emma, driven to loneliness, befriends Harriet, an orphan girl from the local girls’ school.

Having met this close friend, Emma is constantly on the lookout for a marriage partner for her, desperate to bring her together with the Reverend Elton. This matchmaking behaviour upset one of her father’s friends, Knightley, who on many occasions repeatedly criticised Emma’s meddling and accused her of being a self-righteous young lady.

For a time Emma thought that she was behaving very reasonably towards Hartley and Elton in setting them up, and for a time she thought that the two were about to make their feelings known, and even had Harriet turn down a serious proposal from Robert Martyn for this reason.

Who knew that after another party, Elton would state that he had never had the lowly Harriet in mind, and would instead pursue Emma with single-mindedness. This outcome is unexpected for Emma, but she doesn’t give up on finding a new man for Harriet, this time trying to get the posh Frank Churchill to fall in love with Harriet.

Emma is a good-looking and somewhat mean-spirited character in the film

Her arrogant attitude once again upsets Knightley, and after a stern reminder that she has hurt a lot of people with her petty and condescending attitude towards others, Emma begins to change and make amends with the unintentionally hurt Miss Bates family. She also comes to realise that her feelings for Knightley are very complicated, and after several misunderstandings, Knightley and Emma exchange feelings and make a marriage. Harriet also re-accepts Robert Martyn, and this time Emma’s matchmaking is quite successful.

It is not uncommon to see this kind of love affair, from meeting to misunderstanding to resolving the misunderstanding, and the marriage of a country squire and a rich girl is a perfect match. And the film Emma. is both faithful to the original and innovative: for the most part it follows the original narrative, but the newness of the individual episodes is even more striking.

The use of seasons as a subplot

In the romantic episode where Knightley confesses his love for Emma, everyone is engrossed in the ambiguous atmosphere and looks of panic, and they can’t help but blush from across the screen. –The uncontrollable physical reaction to the excitement and tension of such a special moment is naturally more reflective of the true feelings of the heart than any expression or confession. This sense of humour becomes the deserved climax of the piece, adding a new dimension to the confession sequence. Emma is also portrayed more like a real girl who would blush and have a nosebleed at the sight of a handsome man, much closer to you and me in life.

The prom sequence is very ambiguous

Interestingly, in an interview after the screening, Anya Taylor-Joy told the audience that the ‘nosebleed’ scene was a surprise, as it had not been in the script, but was a real bleed in her own performance and the director thought it was a good performance instead, so he left it in and made it a highlight.

English country: bright tones and songs

Although there is nothing outstanding in the plot, the film has got everything right, with stunning colour schemes and compositions reminiscent of Wayne Anderson’s OCD, and Emma’s dazzling costumes reminiscent of the fashion show in The Greatest Showman.

Alexandra Byrne, a four-time Oscar nominee for Best Costume Design, made a big impression with Elizabeth in 1998, and in this case Emma. in which everyone’s costumes are even more exquisitely and historically relevantly handled.

The opening scene of Mr. Knightley’s entire costume change, in which Knightley is shown in nearly two minutes, from his riding attire to his formal dress for a meeting, is structured and period-specific, and serves as a point of entry into the dress of the early 19th century English gentry.

The symmetrical composition and candy-like colour palette are the highlights of the film

Emma and her companion Harriet’s dresses are very similar in general terms, but there are many differences in detail. Emma’s family was wealthy and her clothes are more patterned, with rich layers of ruffles and lace and very fine workmanship, whereas Harriet’s dresses are relatively homogeneous, with a single garment repeated on many occasions, and the colours are less saturated and overly gaudy in a variety of colours.

The contrast between the hats is even more striking, as Harriet has only a ribboned straw hat, while Emma uses the same colour palette for different outfits, and the hats for walking and worship are very different, with heavier materials and very elaborate feathers and lace embellishments, making the overall design far more complex than Miss Harriet’s hats.

The soundtrack is also very commendable: the combination of English folk and religious music is perfectly suited to the changes in the plot, and the clear voices that appear in each transition pull the viewer from the screen to the English countryside. The lightness of pace is also in keeping with the film’s light comedy, with a duet between Jane Fairfax and Knightley making the most of the laid-back mood of the ballads and parties. The pacing is just right for this film, where the plot is not the focus of Emma. The atmosphere and the emotional ambiguity are necessary in the film.

A mediocre review: can old themes be revived?

Austen’s story has been badly filmed, and no matter what attempts are made to detail Emma. The story is not as good as Austen’s, and no matter what attempts are made to detail it, the unbreakable romantic comedy formula still limits the scope of play, and is much less visceral than the deeper exploration of characterisation and femininity in last year’s Little Women, which also explores class divisions in a superficial way, making it hard to get a higher rating.

The lack of a filter on Austen’s work for many domestic audiences compared to the British made it even more so with a very mediocre 7.0 rating on Douban. It has few bad reviews but not many good ones either, and is probably best described as “middle of the road”.

The composition of the film is like an oil painting with a single cut

Compared to the star-studded cast of 2005’s Pride and Prejudice, Emma. The casting is very plain, and the heroine’s best friend, Harriet, is a simple girl who moves in a bit of a panic, with light eyebrows that make her look exaggerated and timid in contrast to the heroine’s somewhat mean-spirited demeanour.

This somewhat timid and panicked look is not beautiful, but it makes her very relevant: an orphan girl of no mean status, a trait that is particularly evident when she is alone at the ball, when everyone ignores her and the friend accompanying her is the star of the show, and Harriet is left sitting on the sidelines, too nervous to cry, too timid to even move. This restraint at the ball contrasts with the ease with which she has fun with her classmates at boarding school, and the difference in character due to class divisions is evident throughout.

But despite this, the film’s portrayal of the characters is limited to what is given in the book, with the conceited Emma transforming so abruptly when she realises her arrogance that the characters become faceless, and Mrs Fairfax and Elton being portrayed only in a rushed but less vivid manner. As a romantic comedy, the characters are ‘adequate’, but Emma. still has a long way to go.